And then the rumblings began

In 2010 The Southern Series Events Manager Hugh de Lacy was commissioned by the Golden Shears Society of Masterton, New Zealand, to write a decade-by-decade overview of the wool industry for the society’s commemorative book “Shear History: 50 Years of Golden Shears in New Zealand” (Fraser Books, R.D. 8, Masterton, NZ). Though specific to New Zealand’s predominantly strongwool industry, it reflects the many travails the global wool industry has endured since the end of World War Two. Here’s part two, the 1970s.

By Hugh de Lacy (snr)

The 1966-68 collapse in wool prices convinced the Wool Board and the wider industry that the Wool Commission model of propping up auction prices – and indeed the auction system itself – had passed their use-by date. The commission floor price had further sunk by the 1970-71 season to 21 cents a pound, now expressed in decimal weights as 45 cents per kilogram.

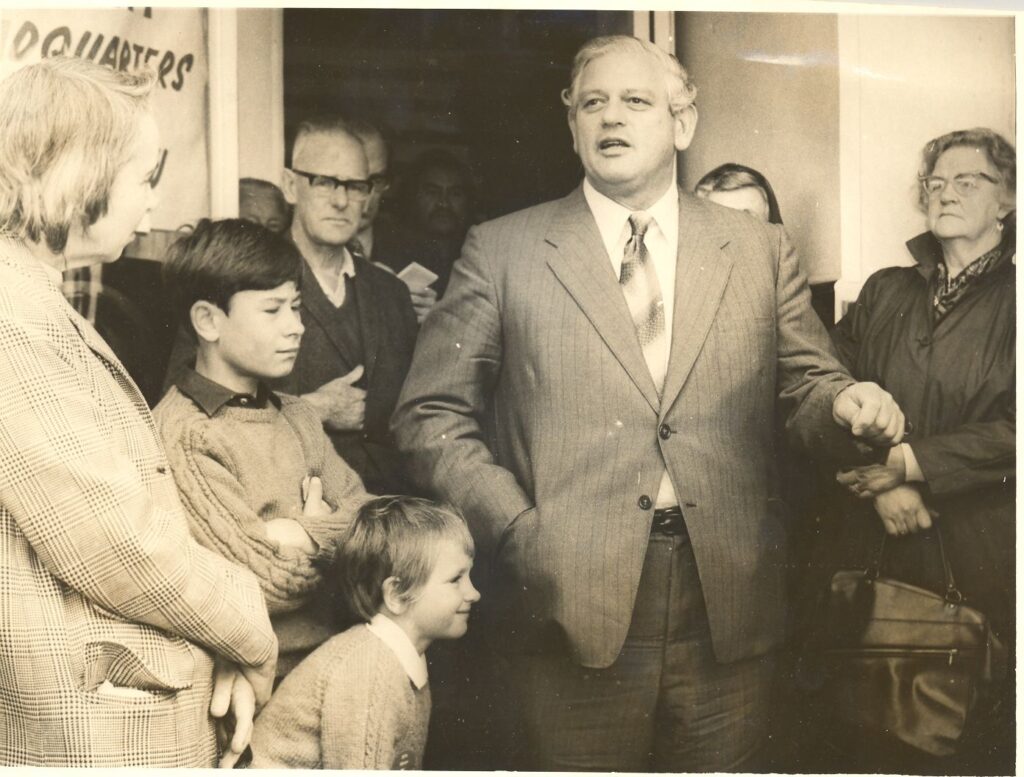

Times of turmoil: Norman Kirk, courtesy of the Horowhenua Historical Society Inc.

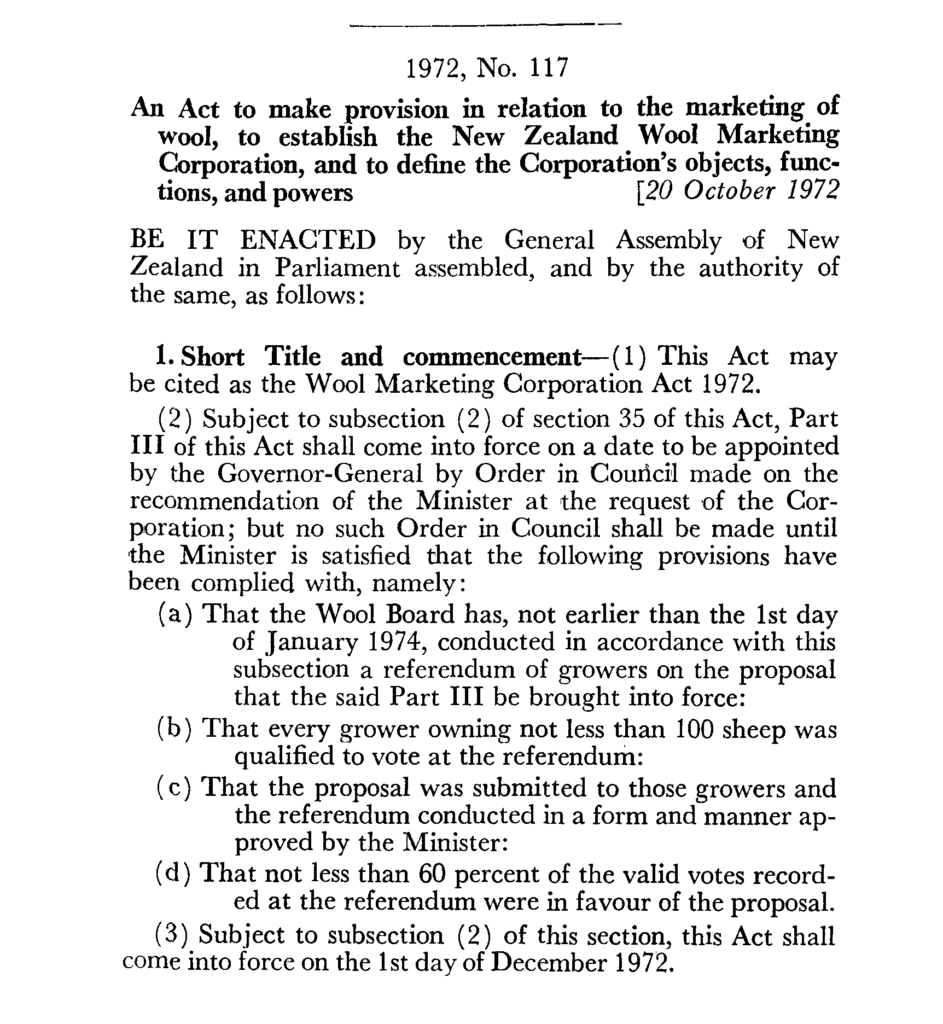

In search of a replacement strategy, the Wool Board had decided to hire outside consultants for the first time to come up with a way of marketing the national clip that would extract the best possible prices from wool’s shrinking share of the global spend on fibres. The job was given to an American consultancy, the Battelle Institute of Ohio, which in 1971 came up with the notion of replacing the Wool Commission with a new marketing authority called the New Zealand Wool Marketing Corporation. Its job would be to market wool more directly between the woolshed and the end-user, hopefully cutting out what was perceived to be a chain of intermediary ticket-clippers.

The corporation was to be given wide-ranging powers, from making the supply chain more efficient, to negotiating shipping rates and developing new and existing markets. This was pretty much what the South African wool industry had already instituted in the apartheid republic and, despite initial farmer scepticism, it seemed to be working there.

Though not specifically proposed in the report the Battelle Institute presented to the New Zealand Wool Board in August of 1971, implicit in its recommendations was the need for the overwhelming bulk of the national clip to pass into Wool Corporation ownership for subsequent disposal. Though clearly the nub of the proposal, the means of acquisition was inadequately canvassed, especially among the farmers who owned the wool and whose complicity was vital.

By degrees the Wool Board reached the conclusion that acquisition would have to be compulsory, and to that end it went as far as negotiating the required legislation with the National Government of the day. Though the Cold War between capitalism and communism was at its height, and compulsory acquisition smacked of something dangerously socialistic, the concept initially ran into few hurdles, and by the end of 1971 the decisions had been taken to replace the Wool Commission with the Wool Marketing Corporation, the Battelle Report had been endorsed unanimously by the Wool Board, and both Parliamentary political parties supported it. When the Wool Board in May of 1972 put the proposal to the 25 members of the Electoral Committee of the Meat and Wool Boards, elected by farmers to oversee the twin sheep industries, there was only one dissenter. Federated Farmers too was wholly behind the scheme.

Confident they had the backing of farmers, the board and the Government headed off down the road to compulsory acquisition of the entire wool clip by the new entity, the Wool Marketing Corporation, which was formed in 1972.

And then the rumblings began.

Initially starting with individual farmers expressing their concerns through newspaper letters and advertisements, opposition to compulsory acquisition began to mount. And it snowballed. Local action committees sprang up all over the country and eventually flowered into two national organisations, the Wool Action Group and the Sheep and Cattlemen’s Association, which severely undermined Federated Farmers’ position as the main medium through which workaday farmers expressed themselves politically.

Had the Wool Board at this juncture come down from its Featherston Street mountain to talk with the farmers in the field about the rationale behind compulsory acquisition, it’s possible acceptance might have been won for what was, by New Zealand standards, a radical innovation. But the more the opposition mounted, the more entrenched and dictatorial the board’s position became.

The tipping point probably came at a meeting in Waipukurau, Hawke’s Bay, attended by no fewer than 550 farmers. The truculent tone of the meeting was set by Wool Board member and millionaire carpet manufacturer Doug Bremner showing up in his Rolls Royce to tell farmers that compulsory appropriation of their wool by a statutory authority was the only alternative to poverty. Needless to say his message was not received sympathetically.

The upshot of the whole row was the defeat of the Wool Board proposal and the ousting of most of its proponents by Wool Action Group and Sheep and Cattlemen’s Association members. At the end of 1972 the Government itself got the boot, replaced in a landslide general election by the Norman Kirk-led Labour Party.

Eventually, in 1978, the Wool Board and the Wool Marketing Corporation were amalgamated, and the floor price concept continued, with farmers being paid the difference between it and the auction price if the latter was lower. The money for this came from a one per cent levy on wool that sold for more than the minimum price. Compulsory acquisition remained an option for the amalgamated body but it would have required a farmer referendum to implement, and since that was now less likely than ever, it remained a dead issue.

Battelle and the Wool Board had been correct in defining ownership of the national clip as the key to enhancing the value of New Zealand’s predominantly coarse wools, but the board had completely botched the marketing of the concept to the farmers who owned the wool.

In hindsight it’s clear that the concept of a compulsory takeover of the ownership of their wool was anathema to most farmers. What might have worked was a farmer-owned co-operative taking by persuasion rather than compulsion a big enough slice of at least the crossbred clip to dominate the market, with the mid-micron and finewool sectors running parallel companies, and a cluster of privately-owned companies keeping them honest. That way the hundreds of different wool types could have been enhanced by pooling into consistent and specific lines at central depots, where it could be scoured, and then marketed direct to manufacturers. That would have circumvented the neanderthal system of sale by auction, and provided a direct link between farmers and the manufacturers who used their wool. Over time the co-operatives could have invested in their own manufacturing capability, thereby creating the vertical integration which is the ultimate strength of the co-operative business structure.

Compulsory acquisition might have seemed simple enough to the mandarins and politicians of the nanny state that was New Zealand in those days, but sheepfarmers then were not prepared to be nannied, even for their own good.

All this passed serenely over the heads of the shearers who blazed on regardless, more concerned about the impact on their travel costs of the first oil crisis in 1973 than the political games being played in Wellington.

What shearers did notice though was the changes in the sheep they were shearing. Sheep numbers continued to climb, reaching 69 million in 1980, and more and more of them were open-faced. By then there were 11 million each of Perendales and Coopworths, and together they comprised 35% of the national flock. Romney was still the dominant breed but numbers had fallen to 28 million, or 45% of the total. Corriedale numbers had risen to five million (just under 8%) while Halfbreds were slightly up at 2.4 million (3.8%). The Merino flock had grown to nearly 1.3 million (2%). Crossbreds had slumped to just 775,000 (1.2%), while English Leicesters, Southdowns and Ryelands had virtually disappeared under the radar.

The other thing shearers noticed in the 1970s was the rise in second-shearing, either six-monthly or eight-monthly. This was soon to create an over-supply of shorter-length wool, but between 1970 and 1980, along with increased sheep numbers, it cranked up farmers’ total spend on shearing from just over $25 million to just under $117 million. Over the same period shearing expenses as a proportion of farmers’ income from wool dropped from 19% to 16%.

Second-shearing turned the shearing industry into a year-round operation for the first time, and it was no coincidence that this period saw the rise of the first super-athlete shearers, the likes of John Fagan and Hamahona (Sam) Te Whata whose big-tally battles hoisted the lamb record to over 600 a day. What was known as a New Zealand circuit developed in which shearers began the year with the South Island main-shear from January to March, then headed to the North Island for the second shear, calling in at the Golden Shears on the way through. Then it would be back down to the South Island about June for pre-lamb shearing, which also increased during the decade as farmers realised the value to their wool of avoiding the break in staple caused by the lambing check, and the better mothering their ewes were capable of when carrying no more wool than their lambs. By October the migrant circuit shearers would be back in the North Island for the dry and main shears there. The dry – or hogget – shearing has since diminished greatly as more farmers put their replacement ewes to the ram, where previously they had given them a year to mature before being mated.