A bouyant surge on the

back of a hangover

In 2010 The Southern Series Events Manager Hugh de Lacy (snr) was commissioned by the Golden Shears Society of Masterton, New Zealand, to write a decade-by-decade overview of the wool industry for the society’s commemorative book “Shear History: 50 Years of Golden Shears in New Zealand” (Fraser Books, R.D. 8, Masterton, NZ).

Though specific to New Zealand’s predominantly strongwool industry, it reflects the many travails the global wool industry has endured since the end of World War Two. Here’s part one, the 1960s.

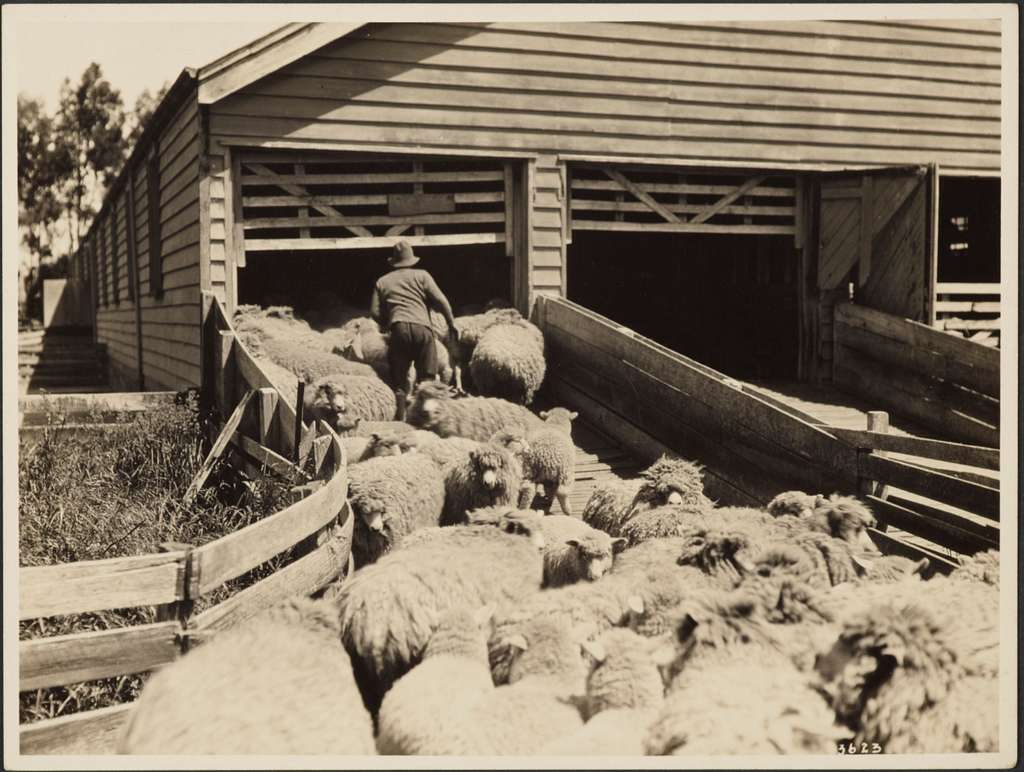

Boom and bust: Things were different back then. Picture courtesy of GetArchive, public domain.

By Hugh de Lacy (snr)

Several factors drove confidence in wool in the decade and a half following World War Two. The first was the unexpected ease with which the huge stockpiles of wool held in Britain at the end of the war were liquidated at substantial profits. There had been fears that the stockpile would dampen prices for a decade or more. Nearly 1.5 million tonnes of wool had been stockpiled, 245,000 tonnes (17%) of it from New Zealand. It had been accumulated as much to stop the Axis forces from getting it as to meet the Allied needs, and its size can be appreciated in the context of New Zealand’s total annual production during the war being around 160,000 tonnes.

To dispose of the stockpile, a Joint Organisation was formed in 1945 by Britain, Australia, South Africa and New Zealand, which started out with 10 million bales (1.8 million of them from New Zealand) and the goal of selling two million of them a year. It seemed a highly optimistic goal but in fact it was realised by early 1952.

The second factor that gave the wool industry confidence in the early1960s was the hangover from the brief but phenomenal boom created by another hot conflict in a cold climate: the Korean War of 1950-53. Wool prices had peaked in 1950-51 at “a pound a pound” – 240 cents per 0.453 of a kilogram, or around $5.30 a kilogram. That’s more than a dollar higher than today’s prices even after half a century of inflation. The equivalent in today’s terms, taking inflation into account, would be $152/kg. In fact only six bales of wool was bought at a pound per pound, and prices came back to earth with a thud the following season, but it left a legacy of expectation that the future of wool was assured. The 1950-51 average wool price was 224 cents/kg, or $64.18/kg in inflation-adjusted 2009-10 dollar terms.

Further boosting wool’s outlook had been the resumption of promotional work by the International Wool Secretariat (IWS), of which New Zealand was a member along with Australia and South Africa. The IWS had established full-time offices in 15 countries, including the key United States market where it worked in conjunction with the American Wool Council and its Wool Bureau. New Zealand’s Wool Board, formed in 1944, was a key supporter and funder of the IWS.

Then there was the apparent success of the Wool Commission in underpinning the prices New Zealand farmers received for their wool at auction. The commission’s capital had come from the profits from the sale of the war-time stockpile, and its first real test was in the 1957-58 season which started with a 30% drop in prices. The commission spent $4 million buying 47,000 bales of wool, and there were concerns about how it would handle the next season’s minimum pricing. In fact its intervention in nearly a third of the sales in 1958-59 worked surprisingly well, and it ended up with a $1 million profit from selling the wool it had bought the previous year.

The relatively confident outlook for wool had encouraged the Wool Board to employ Godfrey Bowen in 1954 as a full-time shearing instructor, though it kept him on a tight rein during the first couple of years of his employment. The previous year the board had spent just £253 ($506) on shearer training, but by 1955 that was up to £10,469 ($20,938). The board took a while to develop much enthusiasm for shearing competitions because it thought they would lead to a drop in shearing standards. Adding woolhandling to the competitive mix, as envisioned by the Golden Shears organisers, helped change the board’s attitude.

Another development that contributed to the sheep industry’s positive outlook in the early 1960s was the advent immediately after the war of aerial topdressing. First with old Tiger Moth bi-planes, and later with purpose-built monoplanes, veteran World War Two pilots created what has come to be called the third pastoral revolution in New Zealand. The first pastoral revolution, beginning in the 1880s, had been triggered by the start of the frozen meat trade, and the second, in the 1920s, by the availability of cheap superphosphate from Nauru, which allowed the eastern plains of both islands to be extensively fertilised for the first time. Aerial topdressing took superphosphate to the hill country, and launched a new pastoral golden age based on increased sheepmeat and wool production. A fourth pastoral revolution began in New Zealand about 2001, but it was confined to the dairy industry at the expense of sheep-farming.

It was the third pastoral revolution, triggered by aerial topdressing, that did wonders for the sheep industries, and accelerated changes in the end-uses of New Zealand’s predominantly crossbred wool. Up until the early 1950s virtually all the country’s wool had been destined for use in the apparel industry, with the predominant crossbred types ending up as the coarser styles of clothing, such as tweeds and serges. A fair bit of the crossbred clip went into products like blankets, and since most men still wore hats in those days, there was also demand for coarse wool for felted products. New Zealand Merino finewool comprised only a couple of per cent of the total – these days it’s closer to 7% – while what was to become known as mid-micron wool, produced mostly in the South Island from Corriedales and Halfbreds for knitting yarns, comprised more than a quarter.

It wasn’t until about 1953, in the wake of the Korean War boom, that the future of New Zealand’s crossbred wool began to be linked with interior textiles and carpets. From about this time New Zealand’s crossbred wool became steadily coarser as the carpet market expanded before it and the apparel market shrank behind it.

At the beginning of the 1960s there were 24,000 sheep and beef farms in the country, carrying nearly 48 million sheep. The Romney breed accounted for over 72% of them – 35.4 million – and coarse crossbreds another 12% (six million). Corriedales (2.4 million or 5%) and Halfbreds (2.2 million or 4.5%) represented the mid-micron breeds, while Merinos numbered only 890,000 (1.8%). There were small representations of Border-Leicesters, Cheviots, English Leicesters and Ryelands, while the dominant specialist meat breed of the time, Southdowns, numbered only 700,000 (1.4%).

As yet there was no representation of the two New Zealand crosses, the Perendale (Romney/Cheviot) and the Coopworth (Romney/Border Leicester), that were to eventually to rise to significance. Perendales, developed at Massey University by Sir Geoffrey Peren, had been registered as a breed in 1960 but were still few in number. The bigger Coopworth was still under development at Lincoln College by Professor Ian Coop.

The Romney was by far the most common sheep that shearers encountered throughout the 1960s, with a fibre diameter ranging between 33 and 37 microns and fleece weights of between 4.5 and 6 kilograms. It was a blockier animal than the modern Romney, with wool down its legs and over most of its face. Later, as meat became more important than wool, and as scientists explored the relationship between face-cover and fertility in the breed, it became cleaner-pointed, though old shearers will remember the “boofheads” – sheep with “wool up their noses” – that were common then. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s the Romney’s pre-eminence would be put under threat by the Perendales and Coopworths.

While there was some cause for confidence in the wool industry at the start of the 1960s, much of it had evaporated by the end of the decade. The Wool Commission was not called on to support the market in the first half of the decade, and hadn’t done since the 1957-58 and 1958-59 seasons. But crunch-time came in the 1966-67 and 1967-68 seasons. By then the minimum price had been pushed up from 24 pence per pound in 1952-53 to 36 pence, though the commission’s capital base had been eroded by perhaps as much as 20% through funds being diverted to the Wool Board’s expanding activities.

By now the synthetic fibre nylon, developed by the DuPont chemical company in the 1930s, had expanded beyond the women’s stocking market and by the early 1950s was beginning to encroach on crossbred wool territory in the carpet market. The apparel markets were not spared the impact of synthetics either, with polyester making its first appearance, as Terylene, in 1953. Today polyester is the most widely produced synthetic fibre in the world.

In early 1967 the synthetic wave hit the wool market, and manufacturers simply weren’t prepared to pay the sort of money farmers had come to expect for the natural commodity. Suddenly the Wool Commission found itself bidding on up to 99% of crossbred wools, and up to 84% of New Zealand finewools. By the end of the season it had spent a colossal $63 million buying 650,000 bales. This created a balance of payments crisis for the entire New Zealand economy, and for the 1967-68 season the commission cut the minimum price to 30 pence. Even at that level it ran out of money bidding to keep prices up, and it had to borrow from the Reserve Bank to stay in business.

By the spring of 1967 the system was in a state of collapse. On October 13, which became known throughout the industry as Black Friday, the commission was forced to slash its minimum support price in the new decimal currency to 25 cents a pound. Even at that level the commission was still having to buy wool at auction, and by early 1968 it had accumulated over 700,000 bales. It had problems just finding storage for the stockpile, and much of it ended up packed into old disused dairy factories.

The impact on the country’s economy of so much unsold wool stacked up around the country was profound, and the Government found itself with no alternative but to devalue the New Zealand dollar by nearly 20%. That did have the desired effect of creating a lift in demand that allowed some of the stockpile to be sold off, but it didn’t last long. Wool had hit the skids.

None of this had much effect on shearers: the sheep still had to be shorn. Sheep numbers were also inexorably rising, and by the end of the 1960s decade were approaching the 60 million mark. Even with Godfrey Bowen’s Wool Board-funded shearing schools feeding new skilled workers into the system annually, shearers were in short supply and shearing rates were rising with stock numbers. Conditions for shearers were also improving on the back of the 1962 Shearers Act and the 1963 Shearers Regulations, which set minimum standards for on-farm amenities and accommodation. By 1970 shearing expenses were absorbing 19% of farmers’ returns for wool.

While shearers soldiered on as usual, by the end of the decade the wider New Zealand wool industry was in a state of near panic, and a radical plan to save it would precipitate its breaking down into politically-armed camps, all at each others’ throats.